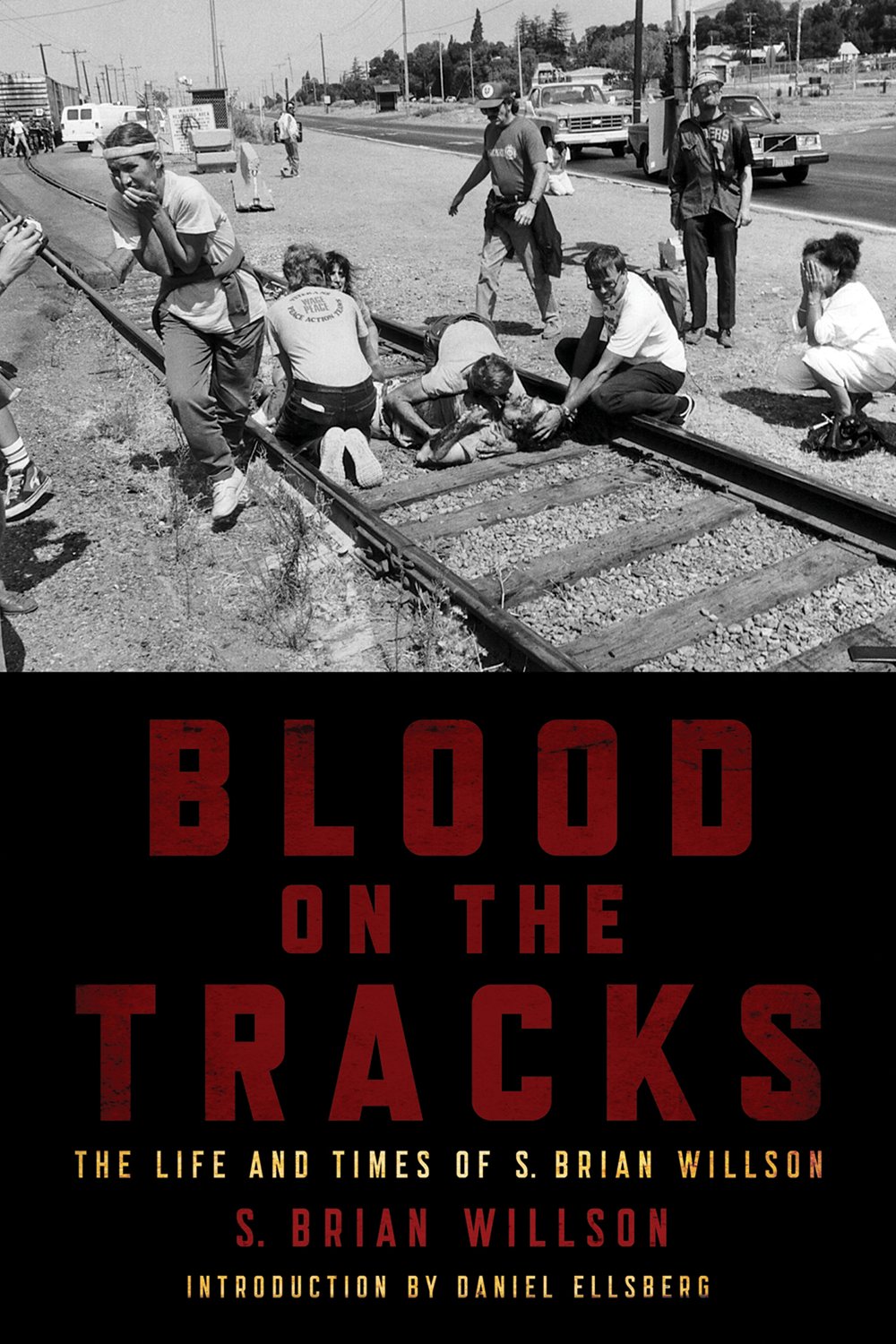

Blood on the Tracks

The Life and Times of S. Brian Willson

“We are not worth more, they are not worth less.” This is the mantra of S. Brian Willson and the theme that runs throughout his compelling psycho-historical memoir.

Willson’s story begins in small-town, rural America, where he grew up as a “Commie-hating, baseball-loving Baptist,” moves through life-changing experiences in Viet Nam, Nicaragua and elsewhere, and culminates with his commitment to a localized, sustainable lifestyle.

In telling his story, Willson provides numerous examples of the types of personal, risk-taking, nonviolent actions he and others have taken in attempts to educate and effect political change: tax refusal—which requires simplification of one’s lifestyle; fasting—done publicly in strategic political and/or therapeutic spiritual contexts; and obstruction tactics—strategically placing one’s body in the way of “business as usual.” It was such actions that thrust Brian Willson into the public eye in the mid-’80s, first as a participant in a high-profile, water-only “Veterans Fast for Life” against the Contra war being waged by his government in Nicaragua. Then, on a fateful day in September 1987, the world watched in horror as Willson was run over by a U.S. government munitions train during a nonviolent blocking action in which he expected to be removed from the tracks and arrested.

Losing his legs only strengthened Willson’s identity with millions of unnamed victims of U.S. policy around the world. He provides details of his travels to countries in Latin America and the Middle East and bears witness to the harm done to poor people as well as to the environment by the steamroller of U.S. imperialism. These heart-rending accounts are offered side by side with inspirational stories of nonviolent struggle and the survival of resilient communities

Willson’s expanding consciousness also uncovers injustices within his own country, including insights gained through his study and service within the U.S. criminal justice system and personal experiences addressing racial injustices. He discusses coming to terms with his identity as a Viet Nam veteran and the subsequent service he provides to others as director of a veterans outreach center in New England. He draws much inspiration from friends he encounters along the way as he finds himself continually drawn to the path leading to a simpler life that seeks to “do no harm.&rdquo

Throughout his personal journey Willson struggles with the question, “Why was it so easy for me, a ’good’ man, to follow orders to travel 9,000 miles from home to participate in killing people who clearly were not a threat to me or any of my fellow citizens?” He eventually comes to the realization that the “American Way of Life” is AWOL from humanity, and that the only way to recover our humanity is by changing our consciousness, one individual at a time, while striving for collective cultural changes toward “less and local.” Thus, Willson offers up his personal story as a metaphorical map for anyone who feels the need to be liberated from the American Way of Life—a guidebook for anyone called by conscience to question continued obedience to vertical power structures while longing to reconnect with the human archetypes of cooperation, equity, mutual respect and empathy.